“...the people who move through the streets are all strangers. At each encounter, they imagine a thousand things about one another; meetings which could take place between them, conversations, surprises, caresses, bites. But no one greets anyone; eyes lock for a second, then dart away, seeking other eyes, never stopping...something runs among them, an exchange of glances like lines that connect one figure with another and draw arrows, stars, triangles, until all combinations are used up in a moment, and other characters come on to the scene... ”

― Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

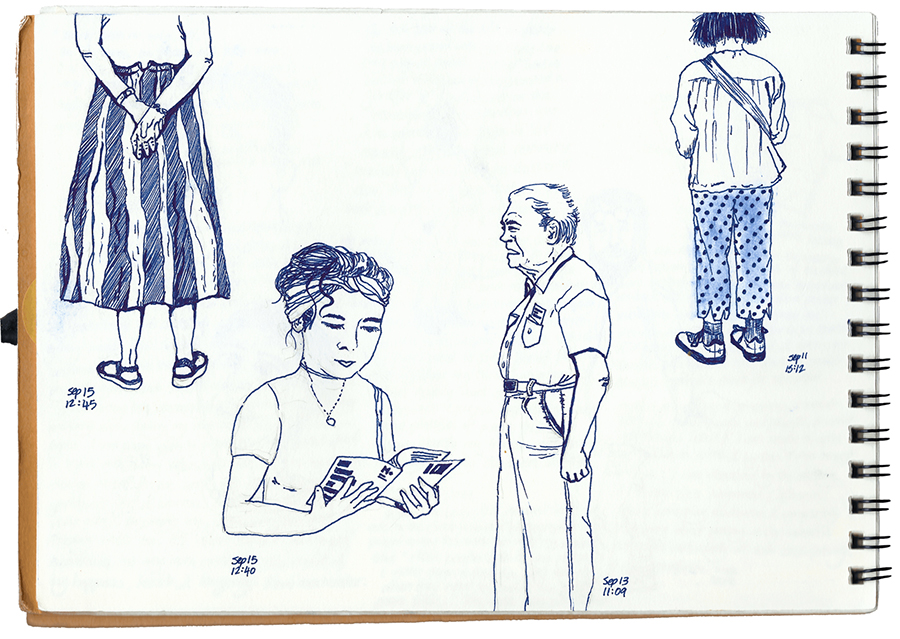

Sketches of visitors at the Hong Kong Pavilion who made an indelible impression on me, be it their impeccable fashion or peculiar comportment in the gallery. Courtesy of Annie Lye

The first Sunday marked our busiest day here since arriving, we had nearly 1,000 visitors stepping through to see “Shirley Tse: Stakeholders, Hong Kong in Venice”. During my internship at the Hong Kong Pavilion which started in September, I photographed countless visitors who saunter through our wooden-door entrance. The photographs captured them in candid freeze-frames and I sketched those who made an indelible impression on me.

***

At ten in the morning, the wooden entrance leading to our pavilion sprawl wide open. Visitors shuffle through to gaze momentarily at the collection of towering fixtures that make up the installations in the courtyard (Playcourt, 2019). Those more daring would slowly, and, with a calculated gait almost, venture to Playcourt and weave their bodies through the gaps of Jade Tongue (2019) and Optic Nerve (2019). Whereas those more hesitant would circumscribe the entire open-air exhibition area, as if being repelled by an invisible force emanating from the two badminton rackets (Imperial and Victoria) bookending the space.

Some mornings, our neighbour’s laundry compliments the colour scheme of Playcourt (2019). Photograph by Annie Lye

Observing the visitors who pass through the Hong Kong Pavilion, I glean muse at human behaviour and interaction between bodies and the space they enter. Pairs of people tend to move through the exhibition space in union, only moving apart ever so slightly and gently when meandering through Playcourt, or when a particular piece of the interior installation Negotiated Differences piques their curiosity. Oftentimes, one would point and gesture at their sightline whilst the other would nod in acknowledgement. Larger groups of families and tours tend to swarm through the doors as a mass-cloud, disperse to various corners of the courtyard then regroup again to migrate to yet another section of the pavilion. A fascinating formation and de-formation performance from the visitors.

An entertaining array of visitors step through the wooden-doors of the Hong Kong Pavilion everyday, be it rain or shine, aqua alta or none. My personal favourite are the happy couple (far right) who wheeled around the pavilion to much delight and shared many smiling moments in each other's company. Photograph by Annie Lye

On one occasion, a sizable group of kindergarten children paid us a visit. We counted around thirty-seven students and were intrepid about the potential incidents that could erupt from having copious number of children around artworks as frangible as Tse’s. Some particularly mischievous children have gone as far as to consider the artwork a monkey bar and charged forwards. Fortunately, these cases have been extremely rare. Though in this instance, not once did their small, energetic bodies get perilously close to the works. Sai Wing (the other Hong Kong intern) and I watched in amazement as the students formed a uniform semi-circle around Francesco Bozza (our Italian colleague) who serenaded them with snippets of narratives about Tse’s works whilst emphasizing to them that one has to always negotiate with the artwork and pass round the extended wooden limbs. Children visitors ask the best questions. Every time a family group visits, the young ones blurt out, “What is this?,” pointing straight at the entanglement of wooden limbs that rise above them. As these forty-or-so bodies filed from one room to the next and finally emerged into daylight, their frenzied furry of forthright queries were always responded to patiently by Francesco.

Francesco Bozza (our Italian colleague) conducting a group of 37-children around Negotiated Differences (2019) by Shirley Tse. Photograph by Annie Lye

As our pavilion is located directly opposite the main entrance of the Arsenale, the generous street (Ramo de la Tana) outside is a popular gathering point for tour groups and the like. We often see inquisitive faces peering into the courtyard whilst the rest of their bodies are hidden beyond the threshold. There are occasions when these bodies make it past the doorway into our pavilion, breaking off momentarily from their main groups. Upon noticing our presence, some would approach us eagerly and request a brief introduction. On one such occasion I asked, “Signora, do you have two minutes to listen?,” to which she trilled, “Sì sì, a short explanation will do. I have to re-join my group outside very soon.”

Sculptor Cynthia Sah and Annie Lye discuss about Tse’s installation Negotiated Differences (2019). Photograph courtesy of Nicholas Bertoux.

The Venice Biennale attracts visitors of all sorts: artists, collectors, curators and critics who visit specifically for this cultural exposition; local high-school students; tourists from across the EU; cruise-ship day-trippers or tour-group travellers, who course through the Biennale in their own pack-like movements. No visitor encounter is ever the same.

Before engaging with visitors, I find it helpful to observe the visitors first and to see where their curious gaze falls on, and engage in a conversation from there. This morning we had a visitor who gazed at the Banksia seed for quite a while, longer than average. I commented to him, “I noticed that you were studying this seed and the wooden pieces meticulously.” He revealed that he was an arborist based in Perth and the Netherlands, and subsequently taught me in identifying some of Tse’s individual wood pieces: Eucalyptus, Balsa, Coconut Palm, Amaranth, Birdseye Maple…

Just when you think you are leading them through a process of seeing the artwork, the roles reverse and the visitors teach you more about the work than you originally knew… Bring them through a process of observation, close observation. Requires parsing through your own knowledge of the artist and artworks, and gathering those facets of knowledge that will appeal to your listeners. Encounters with visitors are an integral part of my role and this excites me. Every new discourse and interaction adds to my own familiarity and appreciation for Tse’s works. I have now spent over 1,500 hours observing, listening and engaging with visitors to the Hong Kong Pavilion. This has made me very conscious of the extensive levels of art-exposure and or experiences one may or may not have had, and hopefully I try to offer a means of understanding. This requires adopting a different point of departure every time, by connecting disciplines, people, interests which first requires a process of observing, listening and engaging.

Left: A father gives his son a piggyback ride through the portal / Right: A mother and newborn visiting the Hong Kong Pavilion (Negotiated Differences, 2019, by Shirley Tse pictured in both photos). Photograph by Annie Lye

The most arresting character, an elderly woman in her late seventies with her bags of groceries, patted me on the shoulder as I was responding to the final questions of another visitor. As soon as she had my full attention, she began gushing out a personal story in rapid waves of Italian, mixed in with Venetian. I am thankful for having studied Italian in university so that I did not have to miss this gem of a story. It moved me immensely. She said she came into the pavilion not caring much for the Biennale itself. But the smell of turned wood emanating from the installation Negotiated Differences drew her in. She began to explain that this familiar smell, this olfactory experience triggered wonderful childhood memories of her as a young girl, watching her father working in the woodwork studio at home. Having moved from Venice to live in the countryside near Mirano, the fragrance is but a fond memory. It made this serendipitous visit to the pavilion a momentary bliss.

Having exhausted her anecdote, the wonderful lady latched onto Francesco and relayed the very same storyline with equal enthusiasm, if not more. With Francesco she found someone who understood Venetian and her enthusiasm soared. After the satisfactory finale she reunited with her groceries and out of the scented room.

An elderly woman in her late seventies recounting her personal story in rapid waves of Italian, mixed in with Venetian. Photograph by Annie Lye

An entertaining series of visitors at the Hong Kong Pavilion. Photograph by Annie Lye

Annie Lye

Annie Lye is a writer and film photographer. Her interests lie in the liminal boundaries between visual arts and architecture.

Currently a research assistant in the Department of Architecture at The University of Hong Kong. In 2017, she curated the photo-documentary exhibition of Rajasthan's Free Medicine Scheme (Slater Concourse Gallery, 2017), which she participated in as a photojournalist. Aside from her photographic pursuits, Lye is also the creative director and co-founder of Bean+Co., a multi-disciplinary creative studio.

Lye received her BA in Interdisciplinary Literary and Visual Studies from Tufts University.